|

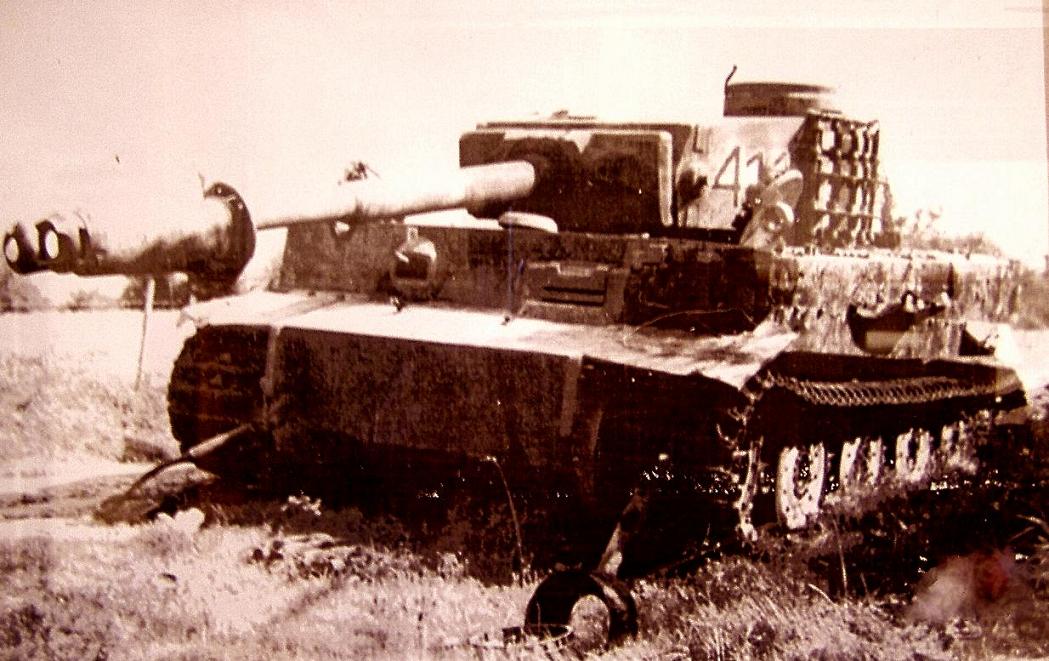

| A knocked-out Tiger tank at Oberwampach, Luxembourg |

Oberwampach

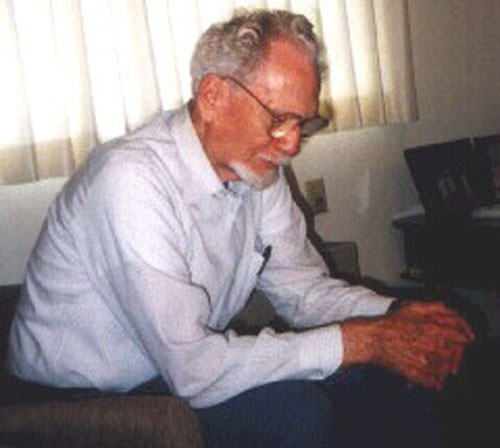

In 1936, Arnold Brown left his home in Cronos, Ky., with 50 cents in his pocket and an eighth-grade education, hopped a freight train, and enlisted in the Army. He was 18 years old. When I interviewed him in 1997, he was 80 years old, a retired colonel, and living in Owensboro, Ky.

During the battle of the Bulge, he was a captain in command of Company C of the 358 Regiment of the 90th Infantry Division. This is his story of the battle of Oberwampach, as told to Aaron Elson.

|

| Arnold Brown, in Owensboro, Ky. |

Arnold Brown

The Battle of the Bulge began on December the 16th, when Von Runstedt started his assault.

We were across the Saar River in Dillingen, and they decided that our position was vulnerable so they had us withdraw under cover of darkness. It was cold, with a freezing rain. We withdrew and occupied a position on land between the Moselle and the Saar rivers, and that’s where we had our Christmas dinner. Then we got orders to move and join the battle in Luxembourg, the Battle of the Bulge.

We loaded on trucks and went up through those mountains, in the freezing cold.

My first operation in the Battle of the Bulge was in the village of Niederwampach.

A and B Company had attacked Niederwampach and were held up, so I was told to go around the left flank and attack from the rear. In a position such as this, I always attacked with two platoons forward and one in support. My position is always in between and slightly to the rear of the two attacking platoons, so I can keep abreast of what’s going on and if I need to commit my support platoon, I’ll know where to do it.

In approaching Niederwampach, the two platoons split up a little bit, so the part of the village in my immediate front had not been cleared. I entered a building with my command group. When I say command group, that was just myself, my communications sergeant, the radio operator and my messenger. We entered the barn part of this building, and when I entered, I turned around and started to say, "I don’t believe there’s anything in here." There was a platform of hay on the right side. The platform was about waist high, and the hay was a little higher than that, and I saw this hay start to move. So we squared off toward the hay with our weapons, and a German said, "Nicht schiessen! Nicht schiessen!" which meant, "Don’t shoot."

I said, "Hande ho. Hande ho." Put your hands up. So they put their hands up and came out and surrendered. There must have been 10 or 12 Germans.

When they surrendered, there was another group of four or five men who came out from the stall behind us, and they surrendered. I heard a commotion over my head and I looked up and I saw there’s a German descending from his rafter, and I noticed that he had hand grenades around his belt, and he came down and surrendered.

To this day I don’t know why they surrendered. I bring it out just to show you how lucky I was all through combat.

I had my other platoons clear out the other buildings, and we captured Niederwampach.

From Niederwampach, we were to go and take Oberwampach, Luxembourg.

Before we left, the battalion commander informed me that the situation was serious, but it wouldn’t become critical as long as we could prevent the Germans from widening the gaps in our lines. They were sending me into Oberwampach, which was on the shoulder of this breakthrough, with the instruction to hold it at all costs. Don’t let the Germans widen the gap. That was my order.

In moving across the open fields to get to Oberwampach, we came under machine gun fire from a position on our right front. So I told the radio operator, who’s carrying the SCR300 radio on piggyback right beside me, to call for artillery fire to neutralize this machine gun. This radio operator now is shot through the head and falls dead at my feet while I’m on the transmitter making that message. There are bullets whizzing around.

We got this accomplished, but instead of getting artillery that time, we had a tank in support, and the tank took care of that machine gun nest.

Another man picked up the radio for me and we took Oberwampach with very little resistance. It was about dusk, and before I got my security all arranged, a German halftrack towing a 120-millimeter mortar and a crew of 12 had moved into our midst. They moved into one of the buildings. They didn’t know we were there and we didn’t know they had moved in, until I sent my messenger back to one of my platoons, and he went to the building where this platoon had originally been. He opened the door, and it was full of Germans.

Two platoons were going into position, so I took my other platoon and gave them the mission of knocking out these Germans, and I told everybody in the company to keep their heads down because we’re going to have a fight right in our midst.

This platoon got in a semicircle around that building, and they opened up on it. They fired a few rifle grenades in it, and when the rocket launchers fired, one of these Germans put up a white flag, and they came out and surrendered. But only six of them surrendered. That’s what the Germans will do sometimes; they’ll surrender some while the others get away, and these other six escaped through the darkness while we stopped shooting.

Well, these Germans were all 6-foot blonds, and they had Adolph Hitler shoulder patches. They were part of Hitler’s elite guard. In other words, up until this time they had been protecting Hitler’s headquarters, and this is the first time I guess that they had actually been committed to hard fighting.

So we were literally fighting Hitler’s supermen. All the same blood type, so if they had to have a transfusion they didn’t have to check it out or anything, they’d just take one man to another.

I questioned them, and found out that they were part of a panzer division that was moving into this area. Based on that information, I asked the battalion commander to send me some more weapons to defend against an armor type attack. He sent me up a platoon of tanks and a platoon of tank destroyers, and I deployed them. And it’s a good thing, because the Germans launched an attack at 3:30 in the morning. If we hadn’t rushed up those tanks and tank destroyers, they would probably have overrun us the first night.

This position we had moved into gave us observation over one of the main routes the Germans were using that had our troops surrounded at Bastogne. So they sent elements of a panzer division to knock us out, and we ended up in somewhere between a 36 and a 72 hour battle, night and day. When the Germans were not making a ground attack, they were bombarding us with artillery fire and direct tank fire. All of their attacks were at night except one. And this was their last attack; I’ll get into that later.

When these battles were going on two of my senior platoon sergeants came to me and they said, "Captain, this is the roughest that we’ve ever experienced." One of them said, "I think we had better withdraw; if not we’ll probably have to surrender."

And I had to tell them that we’re going to hold until the last man. I was no hero. These were my orders. Knowing that at some time, if the Germans got these tanks into our position, we’re out of ammunition and there’s no way we could resist, then I would surrender or tell them to bug out. But I couldn’t tell these men that at that time.

Now these sergeants were brave. They’d fought the Germans longer than I had. They’d fought the Germans in Sicily, in Africa, and now they’d been with me from Normandy in five major battles through the French Maginot Line, the German Siegfried Line, so they were just stating the facts, and I agreed with them. But I had to do what my job was at the time.

So we did hold. And rather than go into a lot of these operations up until the last attack, it was either on the 18th or the 19th of January, the Germans made their main effort to overcome us, and they made this attack in daylight hours.

They hit my right flank where this knoll was that I had a platoon, with four tanks and I estimate a platoon of infantry. Coming across a big long rolling ridge to our front we could count 11 German tanks. There was infantry riding on the tanks. There was infantry in halftracks following over this ridge just as far as we could see, and they were shooting everything they had while they were moving in.

I got on the telephone with the battalion commander, and I asked him to give me all the artillery fire he had available. He turned me over to the artillery liaison officer of the battalion, and the liaison officer asked me to zero one gun in on this target. I had two observation posts set up, one in the right platoon and one in the left platoon, so through them we relayed information. We zeroed one gun in on this target, and the artillery officer said, "Fire for effect."

He had nine battalions – that’s 108 artillery pieces – that hit that target at one time. You never saw such a slaughter in all your life. These Germans didn’t make a tactful withdrawal; it was every tank and every man fleeing for his life. Nothing could have overcome that. It’s impossible. My men were firing standing up, like shooting ducks in a pond, but the Germans were so far away they’d be lucky if they hit anyone.

So the Germans withdrew and they didn’t fool with us anymore.

One other incident took place that I think is of interest.

I had my company command post set up in the home of a family in Oberwampach. We were in the home of the Schilling family. When the Germans were shelling us, a five-year-old boy got excited and dashed out the front door, right into the impact area of the artillery. A 20-year-old soldier dashed out to rescue the little boy. They were both mortally wounded.

The soldier died, and asked someone to rub his left arm, he claimed it hurt him. I did rub his arm, and he turned blue and died.

The little boy died slowly in his mother’s arms, and to see this – you read about these things, but to see the grief this mother was going through of her son being killed by something they had no control over, it really brings some strong lessons to you.

This soldier’s name was Sergeant Whitfield. I recommended him for a decoration and he got it. Now he was a true hero. He gave his life trying not to defend his own life, but to rescue an innocent little boy, and truly he earned his decoration.

He got the Distinguished Service Cross.

After the battle, we also picked up a German soldier who had been wounded. He had been shot in the leg apparently with a .50-caliber bullet, and he laid out overnight in this freezing, subzero weather. Both his arms and both his legs were frozen stiff as a board. He begged us to shoot him. I couldn’t do it. I asked for a volunteer. Even if he survived, he’d have to have both arms and both legs amputated, and this could have been a mercy killing. But these battle hardened soldiers that were fighting Germans a few minutes before would not volunteer. One soldier, out of sympathy for the suffering and bravery of this soldier, lit a cigarette and held it to his lips. Another soldier brought him a hot cup of coffee and held it for him until we got the litter jeep up there and put him on the litter jeep and sent him to the rear. I’ve always been curious to know what happened to him, but I believe he would have died before they got him back to the aid station.

After this battle, the division decoration board section came down and they said that with what happened down there the men deserve some medals. They said, "We want to write you up for a DSC."

And I said, "No." I said, "Every man in the outfit deserves it as much as me and some of them more than I do," and I was really being honest about it. I wasn’t trying to collect medals. I was trying to save as many of these men as I could from getting killed in this terrible war.

- - -

There will be more about the battle of Oberwampach from the perspective of the 712th Tank Battalion in my forthcoming book "The Armored Fist." Email me to reserve a copy. Thanks, Aaron Elson

See how you can help Oral History Audiobooks grow